The Greek Stage

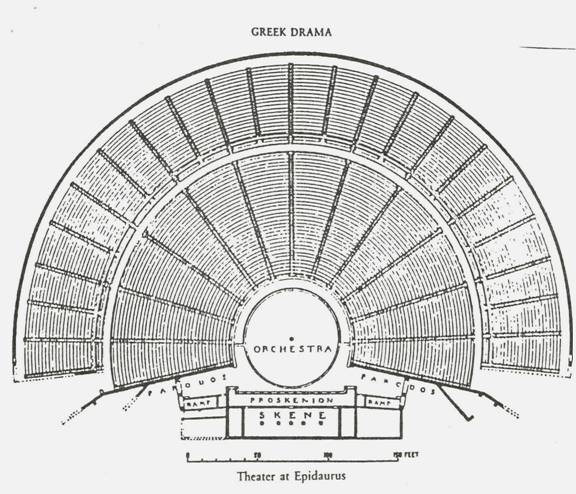

At the center of the Greek

theater was the round orchestra,

where the chorus sang and danced (orches

is Greek for "dance"). The audience, sometimes numbering fifteen

thousand, sat in rising rows on three sides of the orchestra. Often the steep

sides of a hill formed a natural amphitheater for Greek audiences. Eventually,

on the rim of the orchestra, an oblong building called the skene, or scene house, developed as a space for the actors and a

background for the action. The term proskenion was

sometimes used to refer to a raised stage in front of the skene where the actors performed. The theater at

Greek theaters were widely dispersed from

Perhaps the most spectacular dramatic device used by the Creek playwrights, the deus ex machina ("a god from a machine"), was implemented onstage by means of elaborate booms or derricks. Actors were lowered onto the stage to enact the roles of Olympian gods intervening in the affairs of humans. Some commentators, such as Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), felt that the deus ex machina should be used only if the intercession of deities was in keeping with the character of the play. The last of the great Greek tragedians, Euripides (c. 480-C. 406 B.C.), used the device in almost half of his tragedies. In Medea Euripides uses a derrick to lift Medea to the roof of the skene and into her dragon chariot as a means of resolving the play's conflict. At the end of the play Medea is beyond her persecutors' reach and is headed for safety in another country. Modem dramatists use a form of deus ex machina when they rescue characters at the last moment by improbable accidents or strokes of luck. Usually, these are unsatisfying means of solving dramatic problems.

The evidence both in the drama itself and in writings contemporaneous with the plays suggests that attending the theater was usually breathtaking. Besides the complex and sophisticated machinery, playwrights used inventive and colorful costumes and expressive dances. Greek drama combined many arts to produce a truly spectacular experience.

The modern critic Kenneth Burke identified a pattern for Greek tragedies. The tragic figure – who usually provides the name of the play – experiences three stages of development: purpose, passion, and perception. The play begins with a purpose, such as finding the source of the plague in Oedipus Rex. Then as the path becomes tangled and events unfold, the tragic figure begins an extensive process of soul-searching and suffers an inner agony – the passion. The perception of the truth involves a fate that the tragic figure would rather not face. It might be death or, as in Oedipus Rex, exile. It always involves separation from the human community. For the Greeks, that was the greatest punishment.

According to Aristotle, the tragic hero's perception of the truth was the most intense moment in the drama. He called it anacnorisis, or recognition. When it came at the same moment that the tragic figure's fortunes reversed – the peripeteia – Aristotle felt that the tragedy was most fulfilling for the audience. This is the case in the fourth episode of Oedipus Rex. Aristotle's comments in his Poetics on the s t k u r e and effect of Oedipus Rex remain the most significant critical observations made by a contemporary on Greek theater. (See the excerpt from the Poetics on page 93.)

The Structure of Greek Tragedies. The earliest tragedies seem to have developed from the emotional, intense dithyrambs of the kind sung by Athenian choruses. The chorus in most tragedies numbered fifteen men. They were ordinary Athenians and usually represented the citizenry in the drama. They dressed simply, and their song was sometimes sung together, sometimes delivered by the chorus leader. Originally, there were no actors separate from the chorus.

According to legend, Thespis (sixth century b.c.) was the first actor – the first to step from the chorus

to act in dialogue with it – thus

mating the agon, or dramatic confrontation. He

won the first prize for tragedy in 534 b.c.

As the only actor, he took several parts, wearing masks to distinguish the different characters. One actor was the norm

in tragedies until Aeschylus (525?-456 b.c.),

the first important Greek tragedian whose work survives, introduced a second,

and then Sophocles (c. 496-c. 406 b.c.)

added a third. (Only comedy used more: four actors.).

Like the actors, the members of the chorus wore masks. At first the masks were simple, but they became more ornate, often trimmed with hair and decorated with details that established the gender, age, or station of each character. The chorus and all the actors were male.

Eventually the structure of the plays became elaborated into a series of alternations between the characters' dialogue and the choral ode, with each speaking part developing the action or responding to it. Often crucial information furthering the action came from the mouth of a messenger, as in Oedipus Rex. The tragedies were structured in three parts: The prolocue established the conflict; the episodes or agons developed the dramatic relationships between characters; and the exodos revealed the conclusion. Between these sections the chorus performed different songs: parodos while moving onto the stage and stasima while standing still. In some plays the chorus sang a choral ode called the strophe as it moved from right to left. It sang the antistrophe while moving back to the right. The actors' episodes consisted of dialogue with each other and with the chorus. The scholar Bernhard Zimmerman has plotted the structure of Oedipus Rex in this fashion:

Prologue:

Dialogue with Oedipus, the Priests, and Kreon establishing that the plague

afflicting

Parodos: The opening hymn of the Chorus appealing to the gods.

First Episode: Oedipus seeks the murderer; Teiresias says it is Oedipus.

First Stasimon: The Chorus supports Oedipus, disbelieving Teiresias.

Second Episode: Oedipus accuses Kreon of being in league with Teiresias and the real murderer. Iokaste pleads for Kreon and tells the oracle of Oedipus's birth and of the death of Laios at the fork of a road. Oedipus sends for the eyewitness of the murder.

Second Stosimon: The Chorus, in a song, grows agitated for Oedipus.

Third Episode: The messenger from Oedipus's "hometown" tells him that his adoptive father has died and is not his real father. Iokaste guesses the truth and Oedipus becomes deeply worried.

Third Stasimon: The Chorus delivers a reassuring, hopeful song.

Fourth Episode: Oedipus, the Shepherd, and the Messenger confront the facts and Oedipus experiences the turning point of the play: He realizes he is the murderer he seeks.

Fourth Stasimon: The Chorus sings of the illusion of human happiness.

Exodos: Iokaste kills herself; Oedipus puts out his eyes; the Chorus and Kreon try to decide the best future action.

As this brief structural outline of Oedipus Rex demonstrates, the chorus assumed an important part in

the tragedies. In Aeschylus's Agamemnon it represents the elders of the

community. In Sophocles' Oedipus Rex it

is a group of concerned citizens who give Oedipus advice and make demands on

him. In Antigone the chorus consists of men loyal to the state. In Euripides' Medea the chorus is a group of the important

women of